The Book That Incited a Worldwide Fear of Overpopulation

‘The Population Bomb’ made dire predictions—and triggered a wave of repression around the world

:focal(537x371:538x372)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/01/d2/01d2d8b5-f4fd-49e3-8f1c-4321fdfa27b5/img_3471.jpg)

As 1968 began, Paul Ehrlich was an entomologist at Stanford University, known to his peers for his groundbreaking studies of the co-evolution of flowering plants and butterflies but almost unknown to the average person. That was about to change. In May, Ehrlich released a quickly written, cheaply bound paperback, The Population Bomb. Initially it was ignored. But over time Ehrlich’s tract would sell millions of copies and turn its author into a celebrity. It would become one of the most influential books of the 20th century—and one of the most heatedly attacked.

The first sentence set the tone: “The battle to feed all of humanity is over.” And humanity had lost. In the 1970s, the book promised, “hundreds of millions of people are going to starve to death.” No matter what people do, “nothing can prevent a substantial increase in the world death rate.”

Published at a time of tremendous conflict and social upheaval, Ehrlich’s book argued that many of the day’s most alarming events had a single, underlying cause: Too many people, packed into too-tight spaces, taking too much from the earth. Unless humanity cut down its numbers—soon—all of us would face “mass starvation” on “a dying planet.”

Ehrlich, now 85, told me recently that the book’s main contribution was to make population control “acceptable” as “a topic to debate.” But the book did far more than that. It gave a huge jolt to the nascent environmental movement and fueled an anti-population-growth crusade that led to human rights abuses around the world.

Born in 1932, Ehrlich was raised in a leafy New Jersey town. His childhood love of nature morphed into a fascination for collecting insects, especially butterflies. Something of a loner, as precocious as he was assertive, Ehrlich was publishing articles in local entomological journals in his teens. Even then he was dismayed by environmental degradation. The insecticide DDT was killing his beloved butterflies, and rapid suburban development was destroying their habitat.

When Ehrlich entered the University of Pennsylvania he befriended some upperclassmen who were impressed by his refusal to wear the freshman beanie, then a demeaning tradition. Not wanting to join a fraternity—another university custom—Ehrlich rented a house with his friends. They passed around books of interest, including Road to Survival, by William Vogt. Published in 1948, it was an early warning of the dangers of overpopulation. We are subject to the same biological laws as any species, Vogt said. If a species exhausts its resources, it crashes. Homo sapiens is a species rapidly approaching that terrible fate. Together with his own observations, Vogt’s book shaped Ehrlich’s ideas about ecology and population studies.

Ehrlich got his PhD at the University of Kansas in 1957, writing his dissertation on “The Morphology, Phylogeny and Higher Classification of the Butterflies.” Soon he was hired by Stanford University’s biology department, and in his classes he presented his ideas about population and the environment. Students, attracted by his charisma, mentioned Ehrlich to their parents. He was invited to speak to alumni groups, which put him in front of larger audiences, and then on local radio shows. David Brower, executive director of the Sierra Club, asked him to write a book in a hurry, hoping—“naively,” Ehrlich says—to influence the 1968 presidential election. Ehrlich and his wife, Anne, who would co-write many of his 40-plus books, produced the first draft of The Population Bomb in about three weeks, basing it on his lecture notes. Only his name was on the cover, Ehrlich told me, because his publisher said “single-authored books gets much more attention than dual-authored books...and I was at the time stupid enough to go along with it.”

Though Brower thought the book was “a first-rate battle tract,” no major newspaper reviewed it for four months. The New York Times gave it a one-paragraph notice almost a year after its release. Yet Ehrlich promoted it relentlessly, promulgating his message at scores or even hundreds of events.

In February 1970, Ehrlich’s work finally paid off: He was invited onto NBC’s “Tonight Show.” Johnny Carson, the comedian-host, was leery of serious guests like university professors because he feared they would be pompous, dull and opaque. Ehrlich proved to be affable, witty and blunt. Thousands of letters poured in after his appearance, astonishing the network. The Population Bomb shot up the best-seller lists. Carson invited Ehrlich back in April, just before the first Earth Day. For more than an hour he spoke about population and ecology, about birth control and sterilization, to an audience of tens of millions. After that, Ehrlich returned to the show many times.

Ehrlich said that he and Anne had “wanted to call the book Population, Resources, and Environment, because it’s not just population.” But their publisher and Brower thought this was too ponderous, and asked Hugh Moore, a businessman-activist who had written a pamphlet called “The Population Bomb,” if they could borrow his title. Ehrlich reluctantly agreed. “We hated the title,” he says now. It “hung me with being the population bomber.” Still, he acknowledges the title “worked,” in that it attracted attention.

The book received furious denunciations, many focused on Ehrlich’s seeming decision—emphasized by the title—to focus on human numbers as the cause of environmental problems, rather than total consumption. The sheer count of people, the critics said, matters much less than what people do. Population per se is not at the root of the world’s problems. The reason, Ehrlich’s detractors said, is that people are not fungible—the impact of one living one kind of life is completely different from that of another person living another kind of life.

The population bomb

Dr. Ehrlich reviews the case for immediate population control and outlines the responsibilities of the individual and national governments.

Consider the opening scene of The Population Bomb. It describes a cab ride that Ehrlich and his family experienced in Delhi. In the “ancient taxi,” its seats “hopping with fleas,” the Ehrlichs entered “a crowded slum area.”

The streets seemed alive with people. People eating, people washing, people sleeping. People visiting, arguing, and screaming. People thrust their hands through the taxi window, begging. People defecating and urinating. People clinging to buses. People herding animals. People, people, people, people. . . . [S]ince that night, I’ve known the feel of overpopulation.

The Ehrlichs took the cab ride in 1966. How many people lived in Delhi then? A bit more than 2.8 million, according to the United Nations. By comparison, the 1966 population of Paris was about 8 million. No matter how carefully one searches through archives, it is not easy to find expressions of alarm about how the Champs-Élysées was “alive with people.” Instead, Paris in 1966 was an emblem of elegance and sophistication.

Delhi was overcrowded, and would continue to grow. By 1975, the city had 4.4 million people—a 50 percent gain in a decade. Why? “Not births,” says Sunita Narain, head of the Centre for Science and Environment, a think tank in Delhi. Instead, she says, the overwhelming majority of the new people in Delhi then were migrants drawn from other parts of India by the promise of employment. The government was deliberately trying to shift people away from small farms into industry. Many of the new factories were located around Delhi. Because there were more migrants than jobs, parts of Delhi had become jam-packed and unpleasant, exactly as Ehrlich wrote. But the crowding that gave him “the feel of overpopulation” had little to do with an overall population increase—with a sheer rise in births—and everything to do with institutions and government planning. “If you want to understand Delhi’s growth,” Narain argues, “you should study economics and sociology, not ecology and population biology.”

Driving the criticism of The Population Bomb were its arresting, graphic descriptions of the potential consequences of overpopulation: famine, pollution, social and ecological collapse. Ehrlich says he saw these as “scenarios,” illustrations of possible outcomes, and he expresses frustration that they are instead “continually quoted as predictions”—as stark inevitabilities. If he had the ability to go back in time, he said, he would not put them in the book.

It is true that in the book Ehrlich exhorted readers to remember that his scenarios “are just possibilities, not predictions.” But it is also true that he slipped into the language of prediction occasionally in the book, and more often in other settings. “Most of the people who are going to die in the greatest cataclysm in the history of man have already been born,” he promised in a 1969 magazine article. “Sometime in the next 15 years, the end will come,” Ehrlich told CBS News a year later. “And by ‘the end’ I mean an utter breakdown of the capacity of the planet to support humanity.”

Such statements contributed to a wave of population alarm then sweeping the world. The International Planned Parenthood Federation, the Population Council, the World Bank, the United Nations Population Fund, the Hugh Moore-backed Association for Voluntary Sterilization and other organizations promoted and funded programs to reduce fertility in poor places. “The results were horrific,” says Betsy Hartmann, author of Reproductive Rights and Wrongs, a classic 1987 exposé of the anti-population crusade. Some population-control programs pressured women to use only certain officially mandated contraceptives. In Egypt, Tunisia, Pakistan, South Korea and Taiwan, health workers’ salaries were, in a system that invited abuse, dictated by the number of IUDs they inserted into women. In the Philippines, birth-control pills were literally pitched out of helicopters hovering over remote villages. Millions of people were sterilized, often coercively, sometimes illegally, frequently in unsafe conditions, in Mexico, Bolivia, Peru, Indonesia and Bangladesh.

In the 1970s and ’80s, India, led by Prime Minister Indira Gandhi and her son Sanjay, embraced policies that in many states required sterilization for men and women to obtain water, electricity, ration cards, medical care and pay raises. Teachers could expel students from school if their parents weren’t sterilized. More than eight million men and women were sterilized in 1975 alone. (“At long last,” World Bank head Robert McNamara remarked, “India is moving to effectively address its population problem.”) For its part, China adopted a “one-child” policy that led to huge numbers—possibly 100 million—of coerced abortions, often in poor conditions contributing to infection, sterility and even death. Millions of forced sterilizations occurred.

Ehrlich does not see himself as responsible for such abuses. He strongly supported population-control measures like sterilization, and argued that the United States should pressure other governments to launch vasectomy campaigns, but he did not advocate for the programs’ brutality and discrimination.

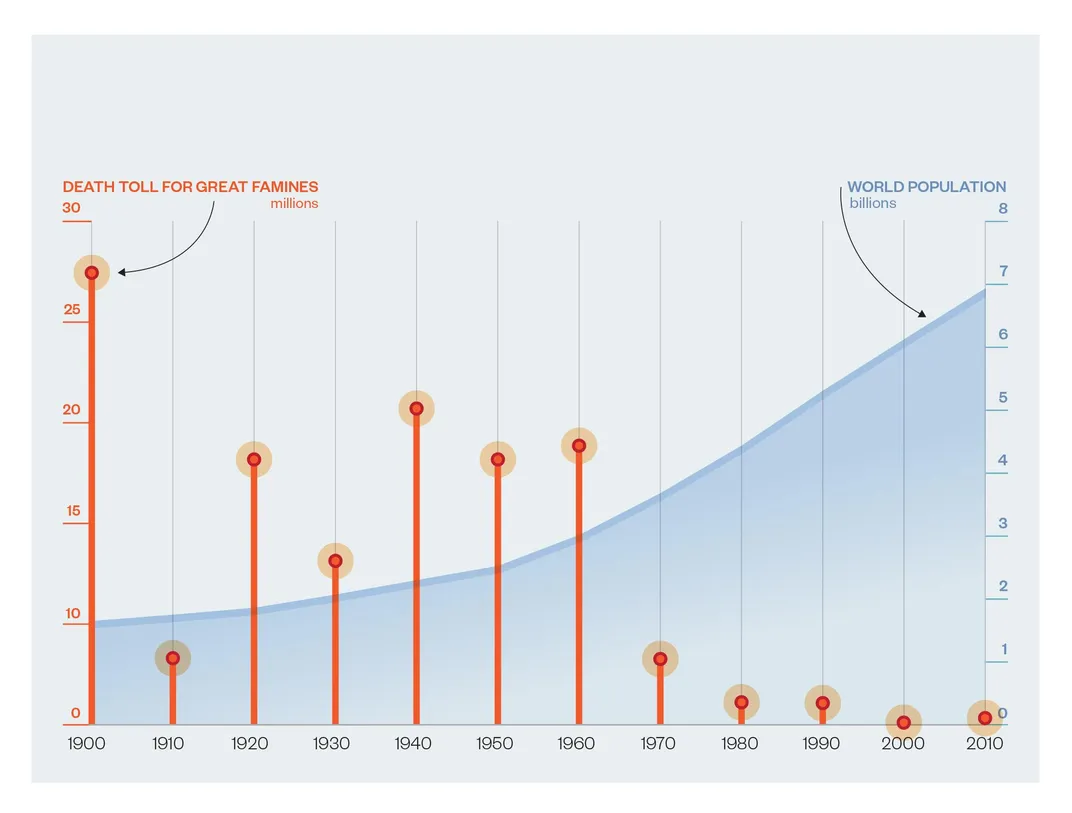

Equally strongly, he disputes the criticism that none of his scenarios came true. Famines did occur in the 1970s, as Ehrlich had warned. India, Bangladesh, Cambodia, West and East Africa—all were wracked, horribly, by hunger in that decade. Nonetheless, there was no “great increase in the death rate” around the world. According to a widely accepted count by the British economist Stephen Devereux, starvation claimed four to five million lives during that decade—with most of the deaths due to warfare, rather than environmental exhaustion from overpopulation.

In fact, famine has not been increasing but has become rarer. When The Population Bomb appeared, according to the U.N. Food and Agricultural Organization, something like one out of four people in the world was hungry. Today the proportion of hungry is about one out of ten. Meanwhile, the world’s population has more than doubled. People are surviving because they learned how to do things differently. They developed and adopted new agricultural techniques—improved seeds, high-intensity fertilizers, drip irrigation.

To Ehrlich, today’s reduction in hunger is but a temporary reprieve—a lucky, generation-long break, but no indication of a better future. Population will fall, he says now, either when people choose to dramatically reduce birthrates or when there is a massive die-off because ecosystems can no longer support us. “The much more likely [outcome] is an increase in the death rate, I’m afraid.”

His viewpoint, once common, is now more of an outlier. In 20 years of reporting on agriculture, I’ve met many researchers who share Ehrlich’s worry about feeding the world without inflicting massive environmental damage. But I can’t recall one who thinks failure is guaranteed or even probable. “The battle to feed all of humanity is over,” Ehrlich warned. The researchers I’ve encountered believe the battle continues. And nothing, they say, proves that humanity couldn’t win.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/SQJ_1507_Inca-Contrib_01.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/SQJ_1507_Inca-Contrib_01.jpg)