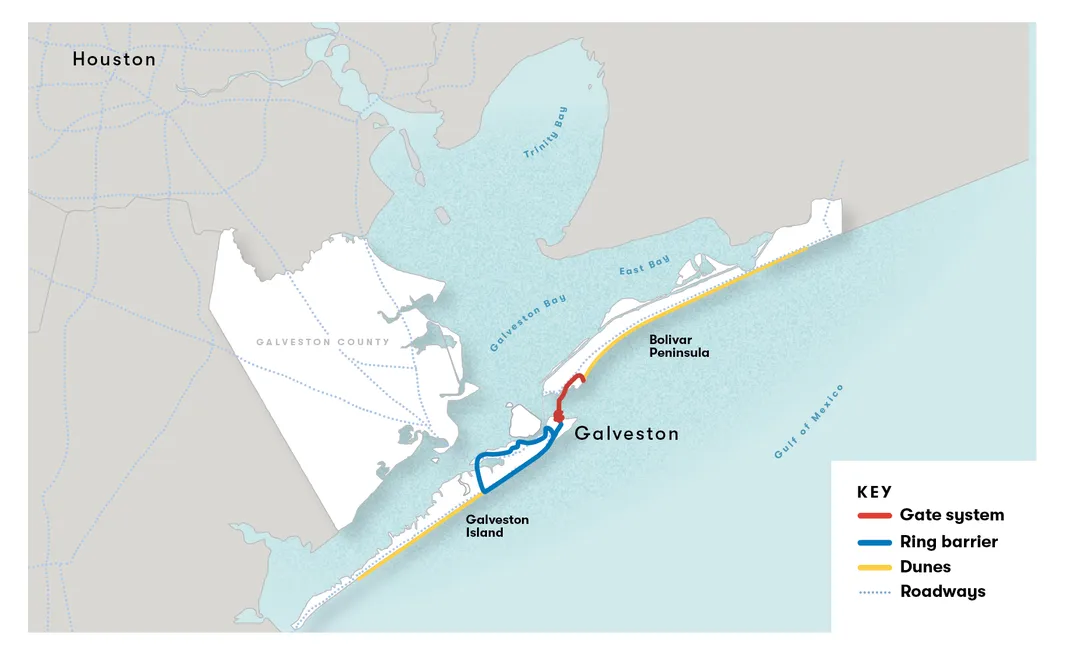

Southeast Texas’ coast is flat and twiggy, bordered mostly by the sea and emblems of the region’s biggest economies—high-rise hotels and oil and smoke-puffing gas refineries. The coastal resort city of Galveston, about an hour’s drive southeast of downtown Houston, transports more tons of cargo than any other port in the United States. It’s a peaceful, watery place. Two long, thin bodies of land stretch toward each other along the Gulf Coast—Galveston Island and Bolivar Peninsula, separated by less than three miles of water at the entrance to Galveston Bay. Each is about 27 miles long and 3 miles wide at its widest point. In between the two is the mouth of the Houston Ship Channel, which provides an estimated $906 billion in economic value to the U.S. each year. Much of that comes from oil and gas entering and leaving the refineries that cluster around Houston.

From the eastern edge of Galveston Island, looking across the bay on an April afternoon, Bolivar Peninsula is barely visible above the sand dunes that line the shore. Cargo tankers stretch far enough to resemble mountains on the watery horizon of the Gulf of Mexico. As tranquil as Galveston may seem, it has been the site of monstrous storms. In September 1900, the Great Galveston Storm flooded the city with a nearly 16-foot storm surge, killing an estimated 8,000 people, to this day the deadliest natural disaster in American history. In September 2008, Hurricane Ike smacked down onto Bolivar Peninsula, destroying 3,600 homes and leaving at least 15 people there dead. More than a million people in the Texas Gulf had to flee, and nearly 2,000 had to be rescued from the storm surge—violent waters thrust up to 20 feet above standard sea levels.

Since then, Texas engineers and lawmakers have been scrambling to find a way to protect the Galveston coastline and the larger Houston region. They’re hardly alone. As climate change brings rising sea levels and as more intense storms batter coastlines, cities along the East Coast, including Miami, Charleston, and the metropolitan centers in New York and New Jersey, are working on plans for expensive coastal-protection projects.

But perhaps no plan is as ambitious—or as ready to go—as the $34 billion project that has emerged in the wake of Hurricane Ike. The coastal Texas project, as it is officially known, draws on techniques pioneered by flood-prone countries like the Netherlands. But it’s been custom-designed for all the different needs of the Galveston coast. Homeowners will be able to look out at sand dunes and restored wetlands, while the city’s business district will be surrounded by reinforced concrete floodwalls. The project’s most ingenious element is a series of 36 sea gates, including two massive gates at the mouth of the Houston Ship Channel, that will seal off Galveston Bay from a devastating surge in the event of an incoming storm. And Texas is due for one. “We have a cycle here of about one every seven years,” says Kelly Burks-Copes, who oversees the coastal Texas project for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. “And it’s been about seven years.”

Burks-Copes, who has a PhD in interdisciplinary ecology and urban-rural planning, and more than a decade of experience on storm-related mega-projects, arrived in Galveston eight years ago. I met her this past spring, when she gave me a tour of the coastline and talked me through the long, complicated journey of the project’s conception and design. With short blond hair and a bright expression, she reminded me of a favorite college professor. “What happened was the storm hit, and a bunch of universities and other entities came up with designs, but nobody could settle on one,” she said. At that point, local Texas governments petitioned Congress to step in, and in 2015 Congress tapped the Army Corps of Engineers to come up with a solution. “We went through all of these plans, and basically drew from them pieces and parts.”

With its patchwork of influences and ideas, the coastal Texas project is unlike anything that has ever been put into practice. Burks-Copes and her colleagues have had to get feedback from a huge cast of characters—petroleum executives and neighborhood environmentalists, ship pilots and academics, federal and state lawmakers. The federal government has promised to pick up 65 percent of the construction costs. Texas will pay for the rest. After a lengthy review process, the final conceptual designs are now set. If the plan succeeds, it could forever change the way Americans mitigate storm damage.

The Army Corps of Engineers has been protecting the nation since the Revolutionary War, when it erected barriers to fortify an area near Bunker Hill. Since then, the corps has helped plan some of the world’s largest bridges and roadways, along with the Washington Monument and the Pentagon. Its projects have included dams that are widely hailed as marvels. But fortifying coastlines against climate change presents a new set of challenges. Congress gave her a mandate, Burks-Copes says: “Look at what everybody else has done and incorporate the good parts into your efforts.”

Galveston has had a seawall since the early 1900s, but the massive waves of Hurricane Ike poured right over it. The first person to put forward the idea of an offshore storm barrier for Galveston was William Merrell, a longtime marine scientist at Texas A&M at Galveston. He likes to tell the story of an epiphany that came to him on September 13, 2008, as he and his wife, daughter, grandson and two chihuahuas witnessed Hurricane Ike’s Galveston landfall from one of two 19th-century buildings he and his family had restored downtown. Merrell has spent his career studying storms—in particular, the physics of the ocean and the impacts of hurricanes. He has earned awards from the National Science Foundation, where he also served as an assistant director. A novel he wrote features the Great Galveston Storm of 1900.

During the storm in 2008, roughly eight feet of water filled the city’s streets; 110-mile-per-hour gales whipped the building’s brick walls. Through the wind’s howl, Merrell’s mind drifted back to a trip he’d taken in the 1970s to the Netherlands, to recruit Dutch researchers for the U.S. Deep Sea Drilling Project, a massive scientific effort that, among other things, helped support the theory of plate tectonics. In his off time, he’d toured Delta Works, an expanding series of flood-protection barriers that the Netherlands had been building since the 1950s. More than a quarter of the country’s terrain lies below sea level, and the earliest examples of flood barriers recorded in that area date back more than 2,000 years. Those barriers—known as dikes—evolved from careful stacks of earth to complex feats of modern engineering.

At the time of Merrell’s visit, engineers were working on the country’s largest and most ambitious barrier project. After a 1953 storm caused devastating floods in the Netherlands, the country launched the Delta Works project, which closed off vulnerable inlets with an array of dams, floodgates, locks and embankments. “Evidently, it imprinted on my mind,” Merrell told me. When he sat down to sketch out a plan for protecting Galveston, he came up with a coastal spine, with barriers and gates inspired by the multifaceted Dutch approach. The plan became known as the “Ike Dike,” a nod to both Hurricane Ike and Dutch engineering. The name was so catchy that people in the Houston area often refer to the current proposal as the Ike Dike, even though it’s significantly different from what Merrell originally proposed, and it isn’t a dike. (Technically, a dike protects land that would otherwise be underwater.)

At first, other scientists argued that Merrell’s plan would be too expensive and complex for the Texas coast. Critics told him he was crazy—to his face, in the offices of elected leaders, and through headlines, which pitted Merrell’s idea against other proposals. “The idea was violently opposed,” he said.

One of Merrell’s most prominent opponents was Jim Blackburn, an environmental lawyer and co-director of Rice University’s Severe Storm Prevention, Education and Evacuation from Disaster Center. “I started off saying it was nuts to put up a coastal barrier,” Blackburn tells me, sitting at a boardroom table in the Houston office of the environmental nonprofit BCarbon, where he’s the CEO. “He reminds me of the heroine in Gone With the Wind,” Blackburn adds, comparing Merrell to Scarlett O’Hara, who famously declared, “As God is my witness, I’ll never be hungry again!” That’s how Blackburn imagines Merrell having his dramatic epiphany: “As God is my witness, it’s never going to flood like this again!” He laughs at the thought.

Not surprisingly for an environmentalist, Blackburn rejected the idea of building walls and gates that would disrupt the natural habitat. He favored a plan that would spend $6 billion on green infrastructure, such as wetlands and human-made barrier islands with gates to help prevent a storm surge. He also emphasized the need for better forecasting technologies—not only to protect homeowners but also to ward off environmental disasters. A Category 4 or 5 hurricane, with at least 25 feet of storm surge, could rip refineries from their foundations. The result would be more than 100 million gallons of spilled oil and other hazardous substances requiring long-term remediation—tenfold worse than the 1989 Exxon Valdez spill, which occurred in a remote part of Alaska. “You could be talking about the worst environmental disaster in U.S. history,” Blackburn says.

The experts were still debating among themselves when local Texas governments finally petitioned Congress to step in. When the Army Corps of Engineers began working on the project, the first step was to meet with the experts. Burks-Copes credits Merrell for being the first to come up with the idea of putting a barrier out in the inlet. “What people tend to do is fortify the shoreline near the big cities,” she says. In fact, this is what Galveston had already tried to do with the ten-mile-long seawall that was built after the 1900 storm. Merrell’s idea, by contrast, was more about “putting a larger defense out front,” she says, not just walling off the land but putting gates at the entrance of the bay. “The idea was to keep the surge from even entering the bay. And that was novel.” Throughout the process, the local experts continued to give solicited (and sometimes unsolicited) advice, but it was up to the corps to come up with a plan.

That also meant making sure the residents of Bolivar Peninsula were on board. Many of the homes have waterfront views. These homeowners didn’t want their properties to flood, but they weren’t happy with the idea of huge structures blocking their views or diminishing the future value of their property. (Despite rising sea levels and increasingly damaging storms, development on the Bolivar Peninsula is growing, including new beachfront communities, hotels and a planned private airport.) “Most of the people that live on these barrier islands and peninsulas came for the sea,” Burks-Copes says. “They came so that they could engage with that kind of environment, day to day and hour to hour. And so you have to be sensitive to that. They’ve invested their lives in this, and so you have to think about how you protect them but still give them the benefits that they moved there for.”

Under her direction, the corps held meetings with neighborhood groups and invited local people to comment on drafts of the plan. When the corps presented its initial vision—with giant sea gates and walls on the peninsula—it got strong pushback in the form of some 13,000 negative comments. A revised plan later received only about 400 substantive complaints. “I call that a win,” Burks-Copes says.

When we toured the coast in April, Burks-Copes talked me through the details of the plan. The easternmost part, she explained, will begin along Bolivar Peninsula. Instead of built structures like sea gates and walls, the corps came up with a different approach: 25 miles of parallel dunes—12 and 14 feet high—separating beachfront homes from the water. “So—big. Really big,” Burks-Copes says. The dunes will be built from sand and sediment that will be dredged from the gulf or local ship channels. This will dramatically change the landscape of this part of the peninsula; homes, which are elevated, will still have a view of the beach, but the beach will no longer be visible from the road, and pedestrians will have to use wooden platforms and staircases over the dunes to get to the shoreline.

Between the dunes, the plan calls for “swales,” shallow channels whose slope will help manage water runoff and create micro-habitats for birds and other wildlife. In front of the dune system, the corps intends to extend the beachfront by 250 feet—actually adding areas for fishing and recreation, Burks-Copes points out. A similar dune system and beachfront extension, running for 18 miles, will protect the homes on the western end of Galveston Island. Because the dunes will erode over time, they will need to be rebuilt every six or seven years.

At the entrance to the bay itself—in the gap between Galveston Island and Bolivar Peninsula—will stand the project’s most impressive engineering feat: a system of 36 gates. The two main gates, nearest the mouth of Galveston Bay, will each be 650 feet wide—two consecutive football fields apiece—and 82 feet tall. Three small islands will be built between Galveston and Bolivar Peninsula to house the gates, which will remain open to ships unless a storm approaches. At that point, the gates will swing shut, fill with water and sink to reach the channel bottom. The gates will be so large that it will take an entire year just to paint each one.

Those two main gates will be supplemented by a three-mile earthen levee, a steel-reinforced concrete floodwall, and two other types of gates, including 15 vertical lift gates that will rise from the bay’s muddy bottom like small skyscrapers pulling themselves up for air. Spanning a total of 4,500 feet across, those 15 gates will be suspended above the water’s surface year-round until they drop into the water to block a surge.

On Galveston Island itself, the city’s entire commercial district will be surrounded by what’s called a ring barrier system. A series of floodwalls and gates, both on land and in water, will seal the city off and protect it from bayside flooding of up to 14 feet. The north and west parts of the area will see construction of a new floodwall of reinforced concrete. In normal times, dozens of gates along the wall will allow car traffic to pass through. During a storm, these gates will slide or swing shut. (Cars will be able to evacuate using a causeway elevated above the floodwall.) On the gulf side, additions to the existing seawall will create a uniform barrier 21 feet tall. (The city is also building new pumping stations in areas that frequently flood, though the pumps are outside the scope of the corps’ work.)

There are still questions about how the whole system will click into action when a storm hits. But Burks-Copes offers a rough idea. She points toward a shrubby spot on one of east Galveston’s banks. There, she says, the corps plans to build one of several centers where operators will constantly gather data on incoming severe weather patterns. As soon as a storm hits the gulf’s warm waters—several days before a potential landfall in the area—the operations centers will send out alerts and trigger a series of responses.

First, ships in Galveston Bay will begin to evacuate as many as 48 hours before a storm makes landfall. That’s partly because of the complex process of timing the shuttering of 36 gates, Burks-Copes explains. Then the closing will begin. “We have to sequence the closing, because every time you close a gate, water gets constrained into smaller places,” she says, which could create its own damaging sloshing effect. The largest gates will require about an hour apiece to close.

Burks-Copes estimates that it will take seven years for engineers to finish designing the gate system. Then it will take at least 12 years to construct the gates, according to the project’s feasibility report. “That sounds enormously long,” she admits. “I get it, because I’m not an engineer, and the first time I heard it, I thought it was pretty long.” For perspective, though, storm prevention systems in Italy, the Netherlands and Russia required about 30 to 50 years to plan and build. “So, this is a very aggressive schedule.” Burks-Copes adds that while the gates are being designed, the corps can get started on other features of the plan. “We won’t be waiting seven years to put something in the ground. We’ll be working on things like beaches and dunes and ecosystem restoration all the way down the coast.”

Of course, construction of any part of the plan can’t begin until funding comes through. Many restless Texans were encouraged in July 2022 after the U.S. Senate authorized the plan. In May 2024, the federal government allocated the first funds for the project—though that amount was only $500,000 out of the $22.1 billion it’s ultimately expected to cover. But locals are encouraged by that small first step.

Nicole Sunstrum, executive director for the Gulf Coast Protection District—a body created by the Texas Legislature in 2021—said her group is “very excited that an initial allotment has been made.” The funding will help the project move from the planning phase into the construction phase, where, she said, it will be eligible for much bigger allocations. “It can take time for authorized projects to be funded, particularly when they are this large,” she noted. “Overall, the response to the project and its merits is very positive—largely because of the human life and supply-chain protections it affords.”

Burks-Copes points out that even the substantial cost of the project is dwarfed by the inevitable costs of being unprepared for the next storm, and the one after that. At the end of May, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration predicted that the coming hurricane season might be the worst in two decades, producing 17 to 25 tropical storms in the Atlantic. About half of those are expected to become hurricanes. “It’s getting more and more expensive to do nothing,” Burks-Copes says. The damages from Hurricane Ike, for example, came out to an estimated $30 billion. The combined cost in Texas and Louisiana for Hurricane Harvey, in 2017, is estimated at $125 billion. Hurricane Ian, which hit southwest Florida and the Carolinas in 2022, cost an estimated $112.9 billion. “If you get this in place,” she says of the Galveston barrier project, “it’s paid for in one storm.”

Some environmentalists remain worried about the impact of the project, especially the gates, which are projected to reduce the flow of seawater in and out of the estuary by up to 10 percent. This could make the water less salty, which would affect animal and plant life. Habitats along the bottom of the ocean will also be destroyed when construction workers dredge the ocean floor to build the gates. Even the color of sand chosen for the dunes is in question due to the habitat of endangered sea turtles, whose hatchlings’ sex is determined by the sand’s temperature. If the sand’s temperature gets above 88 degrees Fahrenheit, the hatchlings all tend to come out female. The darker the sand, the hotter it gets. If the conditions aren’t right, the turtles may choose not to nest there.

Blackburn points to the Netherlands’ Delta Works system as a cautionary tale for how ambitious engineering projects can cause unforeseen environmental issues. The project succeeded in its flood-prevention mission, but in the more than two decades since its completion, marine scientists have found that the ecosystems in at least three areas were damaged. Sedimentation patterns shifted in some places. Coastal erosion increased in others. “There were heavy environmental consequences, at a time when environment didn’t count. It just wasn’t in the equation back when those structures were built,” Blackburn tells me. “It is today.” Of course, the continued health, if not the very existence, of almost all of the Texas coast’s species would be even worse off if a major oil spill occurred in the area as a result of a major storm, like Ike, which narrowly missed the Houston Ship Channel when it made landfall on Galveston Island.

In 2008, when Ike rolled in, I was in my rural Texas hometown in Jasper County, about 100 miles northeast of Galveston Bay, watching the winds bend and break a towering expanse of pine trees surrounding my family’s property. I still remember being unable to distinguish between the thunderclaps and the violent snaps of tree trunks.

Days later, my father and godfather talked our county’s radio station into giving them press passes that allowed them to venture onto Bolivar Peninsula before it reopened to the public. We wanted proof that our modest vacation home and my godfather’s permanent home were gone. They wore vintage fedoras, and my dad carried his 1970s Nikon camera. Law enforcement rolled their eyes and let them pass, telling them they were on their own after dark.

Despite damage to both, our homes still stood—unlike those on much of the rest of the peninsula. I spent time there in the coming weeks and months to help clean up the mess Ike had left. The smell of those days has never left me. The rot within refrigerators that were thrown about the landscape, the constant waft of soggy belongings. The putrid stench of cattle carcasses. The locals who’d permanently left, or who’d stayed but gone missing after the water licked at their homes until they collapsed beneath them. I remember an excess of rodents and snakes scuttling about the area.

Over the years, I’ve traded stories with friends who lived through similar experiences, especially those based in New Orleans who made it out ahead of Hurricane Katrina’s landfall in 2005, when horrified Americans watched the levee failures that killed nearly 1,400 people, displaced a million and caused roughly $125 billion in damages. Katrina remains the costliest natural disaster in U.S. history (adjusting for inflation), but the second through fifth costliest have all occurred in the past dozen years.

When it comes to the Texas coast, a massive storm would affect every single state in the country. Oil and gas prices would soar. And even a temporary closure of the Port of Houston would send shock waves through not only the domestic but also the global economy. “If it’s damaged so significantly that it can’t recover quickly, every state is going to feel this, and they’re going to feel it for a very long time,” Burks-Copes says. “It’s going to cause an escalation of prices everywhere, and not only in the U.S. but out there in the world. That is not even considering how many lives have been lost, or how many livelihoods.”

Before we said goodbye, Burks-Copes admitted that even she, at first, had difficulty grasping the scope and ambition of the Texas project’s goal. “It did take a little while for me to get an understanding of what we’re trying to undertake, and what we were trying to study,” she said. Her gaze across the bay suggested she now grasped the gravity of what her team is hoping to accomplish. She was eligible to retire in May, after 30 years of service, but she isn’t going anywhere.

“I’d like to get the system set up, get the staff set up, and get things rolling,” she told me. “This is the last project I’ll do in my whole career. This will be my legacy. I think. I hope.”